What Happened in Anatomy of a Fall?

my letterbox review was becoming incoherent so i came here.

This probably goes without saying, but, SPOILERS AHEAD.

I had been hearing about Anatomy of a Fall for quite awhile before finally seeing it last month. Friends who saw it were telling me it was one of the best movies they’d seen all year. It won the highest award given out at Cannes, and was nominated in several categories at the Academy Awards (ultimately winning Best Original Screenplay). And of course, I’d seen Messi, the dog who plays Snoop, all over social media.

The first viewing of a movie like this is very different from a second. In the first viewing, you’re going to be holding out to see whether you are ever going to be concretely shown, one way or another, what happened.

In the case of Anatomy of a Fall, you ultimately learn that reveal is never going to come. Which meant, for me, the second viewing I had last week was where I was paying close attention to everything, in the hope that, somehow, I could come to a solid conclusion about what happened.

I know, I know — what happened isn’t necessarily the point; Anatomy of a Fall is about the subjective nature of truth. About how easy it can be to believe you know how something really is or was, even if you’re only being shown small, supposedly cohesive parts of something more complex and nonsensical.

Still, in order to make that point, the film is using an instance in which it’s very important for the truth to be objective: was someone killed, or not? In the courtroom, there needs to be a simple yes or no answer; but as viewers, part of the whole mind fuck is the not. If Sandra didn’t kill Samuel — then what the fck did happen?

The first time I saw this film, I spent the solid first half certain that Sandra did it. She was so clearly uncomfortable, evasive, and, well, guilty. By the end, I genuinely had no idea what to think.

The second time I saw this film, I spent the first half not knowing what to think. By the end, I had arrived to thinking Samuel had genuinely fallen by mistake. Isn’t it right there in the title of the film? The fact that when Sandra suggests it, her lawyer, Vincent, says, “Yeah, but, no one’s going to believe that,” kind of says it all. If that’s what really happened, well — tough shit. This movie is interested in what people believe and why they’re willing to believe it. The idea that Samuel genuinely fell is the least believable option, so nothing we are shown is going to support it as a theory.

Unless.

This time I wondered whether spending so much time on these two opposing theories — murder, and suicide — was not just to undermine them both. Throughout my second viewing, I found myself grouping things into did it and didn’t do it: the fact that Sandra doesn’t want Daniel to see a psychic means she did it. The fact that Sandra watches old recordings of Samuel teaching a class means she didn’t do it. The fact that she has no support system (friends, family) means she did it (she’s a cold, selfish monster). The fact that she doesn’t want her lawyers to talk about Samuel’s depression in court means she didn’t do it (she wants to protect him). The fact that she insists to Daniel that Samuel was her soulmate both means she did it (she is manipulating him), and she didn’t do it (she is empathetically, desperately trying to reconstruct his childhood image of their family).

But in both viewings, my biggest problem was I couldn’t really make sense of either theory. If Sandra killed him in the way the prosecution suggested, then what was the murder weapon, and where is it? If she struck him with something, wouldn’t there also have been blood spatter on the balcony or in the house from the weapon itself? I guess she could’ve cleaned that up, but how did she, mid-struggle, get him over the balcony? And what exactly was her motive? Just a crime of passion? Or she snapped? Over what?

And, even if Samuel truly was suicidal, why would that be the way he chose to do it? Could you even really guarantee you’d be dead from a two-storey fall? I actually find it interesting that Sandra herself seems unwilling to believe Samuel would commit suicide, saying something like, I just can’t get it in my head, that he would do that, and with Daniel so close by. Especially after seeing more fully Samuel’s relationship with Daniel, that feels impossible to me, too — in what world would Samuel want to kill himself in a way that would very likely mean Daniel would be the one to find him, returning from his walk? I also wondered, if Sandra really had killed Samuel, why she would at first resist the suicide theory rather than just going with it. Of course she could be acting, or naive, thinking people would believe he had fallen. But it also just as easily feels she is genuinely trying to wrap her head around something that doesn’t make sense.

Still, there are obviously issues with Sandra. We know she is willing to flat-out lie, and she from the jump omitted something hugely important: the fight between her and Samuel the day before his death. We might also be suspicious of her memory-recalling story of finding Samuel’s vomit with the pills in it. And, of course, there are the affairs, about which she is pretty straightforward and unapologetic. Her motive for killing Samuel could easily be that she just doesn’t like him anymore.

Just the same, there are genuine reasons to be concerned about Samuel’s mental health and what kind of state he was in the day he died. Even without the fight with Sandra the day prior, Samuel was struggling and clearly wasn’t getting the help he needed, as his own psychiatrist seemed to misunderstand mental illness. Though many people associate depression with someone who is sad 24/7 or can’t get out of bed, there are a range of depressive symptoms, including risky and erratic behavior — so it felt very possible to me that Samuel might in fact climb out onto the windowsill for no good reason. Charlotte Wells’ Aftersun does a great job showing that side of depression through Calum’s character, who is introduced to us in an arm cast and at different points in the movie runs in front of a bus and into the ocean at night after drinking. We later learn that, according to Sandra, Samuel had at different times punched the walls of their home (there are photos), and had broken a finger doing just that (we see X-rays). But even without that, we know something is up with Samuel’s psyche from the start of the movie, without ever seeing him; the music blasting on a loop during Sandra’s interview is bizarre and uncomfortable.

The key to this story, and to Sandra’s acquittal, seems to lie in Daniel’s monologue, wherein he says, It feels like if we lack proof to make us sure how something happened, we have to look further, as this trial is doing. When we’ve looked everywhere and still don’t understand how the thing happened, I think we have to ask why it happened. Add to that Justine Triet’s choice for Sandra and Samuel to both be fiction writers, and on top of that, fiction writers who use their real life in their work. The act of imagining events to create or unlock something true is pretty much this story’s whole thing — which is why I believe the closest we can come to “knowing” what happened is to imagine something we haven’t been shown.

The suggestion that we must use our imagination also feels like one of the many functions of the fight scene between Sandra and Samuel. Although the scene is extremely difficult to watch, it’s still wildly satisfying, because it delivers something we’ve all wanted this whole time: if only we could have seen them interact. And, most fittingly, the nature of it, and what was said, was impossible for any of us to imagine. It affects Daniel most of all — as he confides to Marge, he had no idea his parents ever fought like that.

The fight is nasty, brutal, messy, violent — they spare no feelings and don’t mince words. I vacillated between thinking Samuel was unfairly lashing out and that Sandra was completely gaslighting him. I was, like Sandra, wary of Samuel’s claim that he had no time to write, and wondered whether the truer thing was just that he couldn’t write, and wanted to blame that inability on anything or anyone other than him. It can’t be understated how existentially terrifying it is for a writer to not be able to write, so of course not having time is a much easier reality for Samuel to cling to, and he’s only going to dig his heels in further when Sandra calls him on it. Still, I honestly shuddered when Sandra purrs, “Let’s relax. I love you,” and refills Samuel’s wine as a response to his very valid and emotional plea, “Why do you refuse to talk about it? Why can’t you just admit that it has to do with how things are divided between us?” It’s manipulative and even scary. And Samuel is right — Sandra is refusing to have a conversation that is clearly very important to him, and continues to seem inflexible and unsupportive, saying things like “I don’t owe you anything, really,” and “I don’t believe in the notion of reciprocity in a couple, it’s naive, and frankly, depressing.” Of course Sandra is going to be unwilling to admit Samuel could be right about their unfair division of labor — she’s clearly the one benefiting from their arrangement. She’s telling him she owes him nothing, as she eats a meal he made for her. (There’s a throwaway line early on where Sandra says to Vincent she doesn’t know where the pepper is. It could mean it’s not in its usual spot, or it could more likely mean she’s not usually the one cooking.)

My second viewing of this movie was with my brother, who pointed out that if we switched their genders, we would be calling Sandra abusive. I think he’s absolutely right (and Sandra admits to slapping Samuel during the fight, which is assault). Their “gender role” reversal is not an insignificant detail here, which is why I actually find it interesting that in other writing on this movie, I’ve seen people say that Sandra is on trial “as a woman” as much as she is as a murder suspect. I guess this implies that Sandra is being judged so harshly because she isn’t playing the “female role” in her marriage, and we don’t like it when women embody a more “masculine” role. While that might be true, it’s still letting Sandra off the hook; shirking household and childcare responsibilities isn’t inherently feminist, in the same way that “girl bossing” isn’t. Sandra insists she “does her part,” but that sounds a lot like what individuals in the “male role” say when their struggling partner asks for help.

To be honest, I think my own resistance to seeing Sandra as a killer is because she’s a woman, and because it felt inconsistent for Samuel to claim she “imposed” her way of living on them when the circumstances of their lives seemed to be a product of his choices that she merely agreed to. But, that doesn’t mean Sandra shouldn’t also be involved in those choices, like the issue of Daniel’s education, as Samuel seems to be asking for. It’s true that Samuel’s more unfair accusations (they speak English together, he has to renovate the house he wanted them to live in, they’ve never fucked the way he actually wants to) caused me to have doubt in his assessment of things altogether, when that’s objectively not fair of me to do (come on, he’s clearly hysterical!).

Still, we might wonder whether Samuel’s issue lies in the very fact that he is a man in the “female role,” something he hadn’t predicted would happen when he imagined what his life as a writer would be. Sandra asserts that Samuel’s generosity in the relationship “conceals something dirtier and meaner” — suggesting that he might like having the moral high ground of being the one with more household responsibility, so that he can throw it in Sandra’s face whenever he wants. Sandra also believes that Samuel’s own pride and ambition are what make it so impossible for him to face his failures as a writer, and that he’s using their division of labor as a cudgel. Samuel uses his relationship with Daniel as a weapon, too — telling Sandra that even Daniel thinks she’s a monster. He’s told me countless times how hard you are, do you know that? This feels like a pretty cheap shot, and not exactly supported by how we see Sandra and Daniel interact. It’s notable that Samuel deploying Daniel this way is what makes Sandra grow violent.

Regardless of how we interpret it, the fight brings us to the why that Daniel mentioned. Why did this happen? The fight, and Sandra’s interview the next day, clearly have everything to do with Samuel’s death. This brings me to a very important part of my own imagining of what happened: Sandra, at least indirectly, does bear some responsibility. It takes two to tango, as they say.

Even if they were undesirable, I saw Sandra’s actions as genuine. If her sincerity in the courtroom scenes is merely because she’s a good actor, then she would’ve been a good actor in the beginning, too, but she’s not. Her guilt seems pretty clear, as does her discomfort. Even though she’s firm that she didn’t kill Samuel, there’s still something so off about her, and it seems plausible it’s because she does feel somewhat to blame. Knowing the nature of the fight just the day before, I think it would be impossible for anyone to not feel at the very least uneasy if their partner then wound up dead the next day. I think Sandra’s initial resistance to the suicide possibility is also because it implicates her more than an accident does; whatever the true root of Samuel’s depression and his supposed reasons for killing himself were, Sandra is very much tied into them.

There’s one thing that comes up during the trial that I think is another big clue to the role Sandra played in Samuel’s death: it’s when, in being questioned about her cheating, she describes the affairs she had in the year of Daniel’s accident as “not cheating, because Samuel knew about it.” But she also denies they were in an open relationship. Like so much of the dialogue in this movie, this happens quickly, and it wasn’t until the second viewing that it gave me pause. It just seemed like such an odd sticking point for Sandra to have (especially because, in light of the fight, it doesn’t seem like Samuel was fine with the affairs at all), and like a way to re-define within her own mind what was acceptable behavior and what wasn’t: secret affairs are cheating, disclosed affairs are not. Wouldn’t it stand to reason Sandra might decide to define killing someone in the same way? Hitting someone with a blunt object and pushing them over a balcony is killing them; driving them to put their life in danger is not.

The official story is that, after the interviewer Zoe left, Sandra went up to her bedroom, at which point she saw Daniel leaving with Snoop for a walk. We know this is accurate, because we are shown this very scene in the beginning: Zoe going out to her car, and looking up at the house, where Sandra waves from the second floor balcony, as Daniel descends the outdoor steps with Snoop. According to Daniel, he then went back inside the house to get something he forgot — his phone or gloves — at which point he heard his parents talking in what he characterized as calm voices, albeit still with the music playing. Even though we aren’t shown this — we only see Daniel continuing on his outdoor walk with Snoop — it does align with what Sandra says happened next, which is that Samuel came down from the attic to talk to her in her room. According to Sandra, the conversation was “nothing special” — they talked about what they were going to do that day, then Samuel returned to the attic, and Sandra worked on her computer for a bit before taking a nap. An hour later, she woke to Daniel’s screams and Samuel’s body on the ground.

A few scenarios have played out in my head. It could very well be that the conversation was nothing special; perhaps Samuel came down, thinking Sandra would be ready to pick a fight over Zoe having to leave, and she doesn’t take the bait. Their conversation is surface-level, which could in and of itself be the thing that drives Samuel into a worse state: she doesn’t even care, she doesn’t want to have a real conversation, she doesn’t see how upset I am, etc. etc. The fact that Sandra would have such a “flirty” interview (and I do think that’s a fair characterization of it — whether it’s because she’s starved of pleasant conversation or she really is interested in Zoe, we can tell Sandra is trying to steer the interview in a direction away from just interview) the day after a fight in which she was blasé about her past infidelity would easily have been triggering for Samuel, especially if Sandra then refused to engage with him over it. Samuel then could’ve gone upstairs and imagined Sandra not caring if he died, and, seeing the open window, going so far as to sit or stand on the windowsill and picture his body down below. Whether or not he actually intended to kill himself, studies show that mental imagery is causal in an event happening in the future; i.e., if someone imagines themselves doing something, they are more likely to do it, and suicidal ideation in particular is a major risk factor for those with depression. It’s possible that in this state of imagining, Samuel did fall accidentally.

This scenario means Sandra is innocent, but it also means she is probably going to feel guilty for not saying or doing the right things to prevent it from happening. There are many ways to read Sandra’s line after her acquittal, as she bursts into tears over Japanese food and says, I thought I’d feel relieved… it’s just, you know, when you lose, you lose. It’s the worst thing that can happen. And if you win, you kind of expect some… reward? But there isn’t any. It’s just over. Reward is quite the word choice here, but her voice going up as she says it makes me think she’s not quite sure how to describe what she’s feeling in English. Language is certainly a huge part of this film, with Triet noting it was important for the story that Sandra is on trial in languages less familiar to her than her mother tongue — her command of these languages is going to play a big role in how she is perceived, like in this moment. In any case, what Sandra could be trying to say here is, although being found guilty damns you, being acquitted doesn’t absolve you; you might always live with guilt and regret.

This analysis is entering territory I feel needs a disclaimer: it must be mentioned that no one is responsible for their partner’s mental health. There are many instances of people who feel guilted into staying in a relationship they don’t want to be in because they genuinely worry about what their depressed or suicidal or at risk partner might do if they left, and I in no way want to imply that that guilt is somehow founded or fair. This just isn’t the kind of dynamic we see in Samuel and Sandra’s relationship; Sandra never suggests she wanted to leave Samuel, or even that his depression affected her all that much, though it did bother her in regard to the pressure it put on Daniel. And while she claims to have known Samuel struggled with depression ever since Daniel’s accident, she still insists during their fight that his struggles are entirely his fault and that he’s basically just complaining, which, even if it’s how you feel, isn’t exactly the best approach to take with someone you genuinely believe is emotionally and mentally fragile. As such, the guilt I’m implying Sandra has is different.

There are of course other scenarios in which Sandra is less innocent. The calm conversation about nothing could have evolved into another fight after Daniel went back outside. Samuel could have asserted out loud that Sandra is so cold she wouldn’t care if he were dead, and Sandra could have laughed it off, or worse, goaded him: go ahead and kill yourself if you really want to, it’s your choice, just like with writing, no one’s stopping you. This could be her sticking point in what “killing someone” literally means — making light of a suicide threat is bad, but it doesn’t make me a murderer. This, again, could track with her resistance to believing Samuel would commit suicide; if she had thought he would actually do it, she might reason, she wouldn’t have said something like that. It could also be why she doesn’t want to spend a lot of time in court discussing his depression, because it might make it clear she wasn’t taking his mental health seriously. If the previous suicide attempt with the aspirin was real, it doesn’t exactly make Sandra look good.

There also is the scenario where she really does kill him in cold blood. Maybe Samuel comes down, they exchange a few words, and he then says he’s thought about it, and he wants a divorce. He’ll be taking her to court so he can get full custody of Daniel. This was the only scenario I could envision that might drive Sandra into such a state as to kill Samuel to regain control over the situation. Men kill the women who want to leave them all the time. We know Sandra assaulted Samuel the day prior, even if most of what we heard was, as she says, Samuel harming himself, and her, when she tried to stop him. But, like I mentioned before, there is the question of what she supposedly hit him with and how she disposed of it. Then there’s also something even more sinister that no one brought up in the trial — in this scenario, Sandra would have had to go back into her room and pretend to be napping until Daniel came home and happened upon Samuel’s body. I.e., to really make it look like an accident, Sandra decided that her son would have to be the one to find his dead dad. That has to be one of the worst things I could imagine a parent inflicting on their child aside from actual abuse. It makes the murder a far more heinous act than murder itself.

When it comes down to it, I don’t know that I believe Sandra is capable of that, though I know for certain I don’t want to believe she’s capable of that.

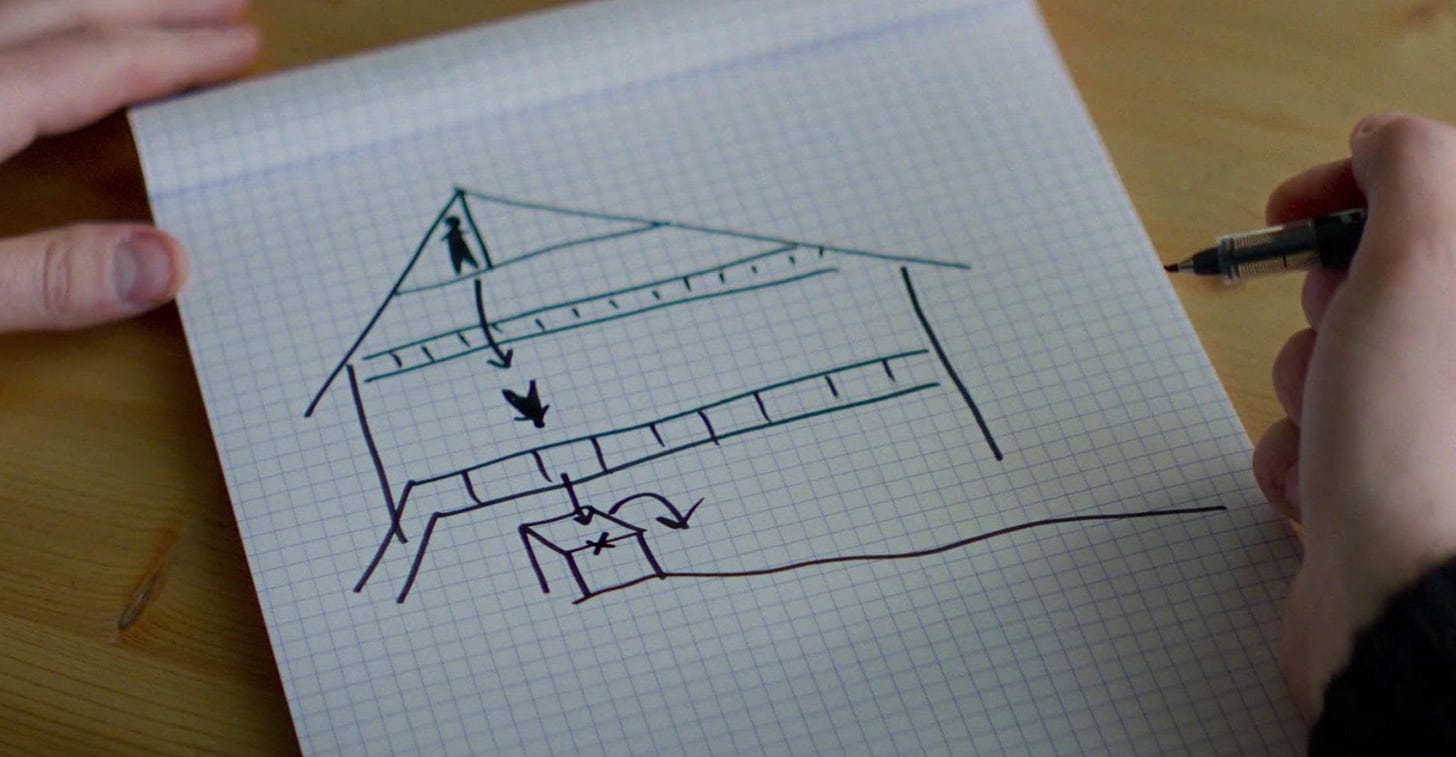

Still, I do think that if she had murdered Samuel, she had more opportunity to make it look like an accident than she did. In the beginning of the film, she gives Vincent a tour of the house, including the attic where Samuel was working. Sandra says the window was open when the ambulance arrived, and Vincent asks if Samuel normally kept it open while he worked. Sandra replies she isn’t sure, though he did sometimes air the room out because of wood dust. Vincent then asks, Was he reckless? Did he ever take risks while working? And Sandra firmly says no — he was cautious and meticulous, and worked slowly. Vincent then asks if there was any reason he would ever lean out the window, like to call to Sandra or Daniel. Again Sandra firmly says no. When he was working, especially when he was playing his music, he, he kind of… he shut himself off from the rest of the world. He never called for me or Daniel up here.

That entire conversation gave Sandra room to say yes. Yes, he always kept the window open, that was quite normal. Yes, he did work quickly and sometimes dropped things or lost his grip. Yes, he had called out to Daniel from the window before. Sometimes he leaned out and called down to me, to get me to come out onto my balcony. It’s possible I didn’t hear him, with the music and my earplugs. But she didn’t say yes. She gave what felt like honest answers either way. No, none of the conditions that would make a fall most ostensible occurred. And so it’s abandoned as a theory.

I said earlier that one of this story’s themes is the idea of imagining something in order to understand or create something true. But I think this film is also getting at something else: just because something is true doesn’t make it right.

Take for instance the debate over the 300-page novel Sandra wrote stemming from a 20-page idea that Samuel had come up with. Sandra says she encouraged Samuel to develop the idea, that she thought it was great. When he didn’t, and she eventually thought of a story that used his idea but with her own spin, he gave her permission to do so. In the fight, however, Samuel accuses Sandra of plundering his work, something the prosecution latches onto. Sandra stole Samuel’s work, therefore it literally is her fault that he can’t write — she took his best idea. Sandra insists this isn’t fair, that Samuel was just exaggerating because they were fighting, when really he was fine with it. Still, I think the more important question might be: even if that’s true, does it make what Sandra did right? Because Samuel is dead, there’s no way to judge how he really felt about Sandra asking him to use his idea. Maybe he felt that since he had done nothing with it, he would seem selfish or unfair in saying no. Maybe he really did think he was fine with Sandra using it, only to eventually regret it and resent her for even asking him. Partners bend to each other all the time — maybe the real issue is Sandra putting him in that position in the first place.

Much of the fight between Sandra and Samuel can be interpreted in the same way. Sure, it’s true that Sandra doesn’t “owe” Samuel anything, and that total “reciprocity” between partners is impossible; but does that make her stance right? Aren’t interpersonal relationships, to their core, about giving? Shouldn’t partners want to give where they can, to the benefit of their relationship / household / family / even themselves? I don’t mean to say we shouldn’t remain individuals with our own priorities; Sandra is entitled to her writing time, but so is Samuel. It’s true that Samuel wanted to homeschool Daniel, and that Sandra didn’t pressure him to do so; but wouldn’t it be right for both Samuel and Sandra to be involved in Daniel’s education, when Grenoble is ostensibly far away and he has a disability? It might be true that Samuel is not a victim — but is that really the right way for Sandra to distill Samuel’s problems? That he is victimizing himself?

I think it’s true that Sandra didn’t kill Samuel. But it might not be right to say she isn’t at fault. As it always does, the truth probably lies somewhere in the middle.

Thoughts? You know where they go, but until next time, this has been —

xxx your twin flame

okay this is a deeeeeeeply satisfying read. i think i need to go watch it again... i think i'm still sticking with my theory that it was simply an accident, and there just isn't any perfect explanation and we'll never truly know what happened. it wasn't suicide, it wasn't murder, it just... was. the conceit of this film feels like a metaphor for grief to me—we try to assign an explanation to something inexplicable because the mind wants to distract itself from processing the event itself. if we can create a simple, digestible container for the event/tragedy to live in, we can make sense of it. we can move on.

ugh, this movie. the intellectual ping pong. who's on trial??! gender!

I hear all of this, and it reminded me of how well fucking written this movie is. None of what was shown or done was accidental; it feels like every part of it the (hot/cool/smart/French) couple thought about while they were hammering out the story and its dialogue. I never thought she did it, but I always wondered if she felt any responsibility, which seems to be your central question. how responsible are we for the welfare of our loved ones? I think that storyline runs parallel with Daniel and his accident, and feels like a thesis of the film. I'm glad you wrote about it!!