Well well well. The time has come at last for me to talk to you about Sally Rooney.

Sally! Everyone’s favorite reclusive Aquarius-Pisces cusp author to love, hate, or claim to be overrated. Wanna know what I think? I think we’re all just jealous, and I’ll get to why we’re jealous later. I also think she doesn’t give a fork what we think and is living in some green ecstasy somewhere in rural Ireland, so.

A few days before I turned 24, Regan texted me a book rec (“I think you’d really like it!”) by an author I’d never heard of. Spoiler alert, it was Normal People, which had just come out in the U.S. I bought it for myself as a birthday gift and read it in two days. I still remember what the light was like coming through my window as I lay on my bed with my feet up on the wall, reading.

There are a lot of things you can’t see that make this moment (me, reading, the color of the light [dark gold]) what it is. There’s the fact that it’s already a weird, melancholy birthday I’m mostly spending by myself; there’s the closeness between where I’m at in my life and where Connell and Marianne are going; there’s my newly acquired knowledge of how it feels to be in love and for it to hurt; and there’s my annoying personality trait where I seldom Love*** anything I read.

***Here, Love means: couldn’t put it down, was moved, learned something, and felt different afterward.

Reader, I Loved Normal People. I loved it like I had never loved a book before.

Then I watched the show the following year, and I loved it even more. It was possible I loved it more than the book.

But wait, is this Substack about Normal People The Book or Normal People The Show?

BOTH.

It’s about BOTH. This Substack is going to get into what makes Normal People such a great book, and what makes Normal People The Show such a great adaptation — and an example of WHY book-to-film adaptations should be done in the first place.

Now, some of you — and I know this because we’ve literally had these conversations before — some of you might be thinking, Conversations With Friends is better! Beautiful World, Where Are You was such a disappointment! Well, friends, to me, and to this Substack, those two titles are honestly irrelevant. My take is simply that Normal People is such a goddamn near perfect book that Sally Rooney need not have written anything before nor since. She could go the rest of her life wordless, or writing entirely garbage, and it wouldn’t matter because of what she did with Normal People.

Okay. I’m picking my mic back up. Let’s begin, shall we?

Normal People The Book

This is my top number one thing about Normal People:

It’s extremely readable.

Like, on a sentence level, it’s just easy to read.

A lot of people may think that easy to read means it was easy to write, and hard to read means it was hard to write. WRONG. A lot of times, it’s actually the other way around: a hard-to-decipher sentence probably means the writer didn’t try all that hard with it.

But it’s one of those self-perpetuating systems, because people love to love stuff that is hard to read. I went through this phase in college, thinking a book was somehow better if it was heady, due to the satisfaction in feeling smart if you find you comprehend it.

But then one day I realized that DFW’s pages of annotations actually pissed me off. And now I’ve regressed to the point that I have pretty much no patience for any intellectual jargon / glibness or lack of clarity. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve put down a book because I’ve stared at a sentence and been like, Literally what are you saying?

There are many people I want to directly call out here but I’m gonna stick to dead white guys, who also somehow convinced everyone a book is better if it’s able to use the word “cocksucking” by page 2.

I look at this and my eyes glaze over. Why are there only three periods?

It’s from The Human Stain by Phillip Roth, which won several awards including the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction. I still have yet to read Phillip Roth (although, that’s bad wording, because what I mean is, I’m never going to read Phillip Roth), but let me ask — did Phillip Roth ever create a literary universe that became an onscreen sensation, launching the career of two of the next generation’s greatest actors?

No. He forking didn’t.

Because this is the thing — Roth and DFW, they’re about sentences for the sake of sentences. That’s where all the fun is for them in being a writer. I honestly don’t think they care about their reader at all. Must have something to do with, idk, male ego competitive BS.

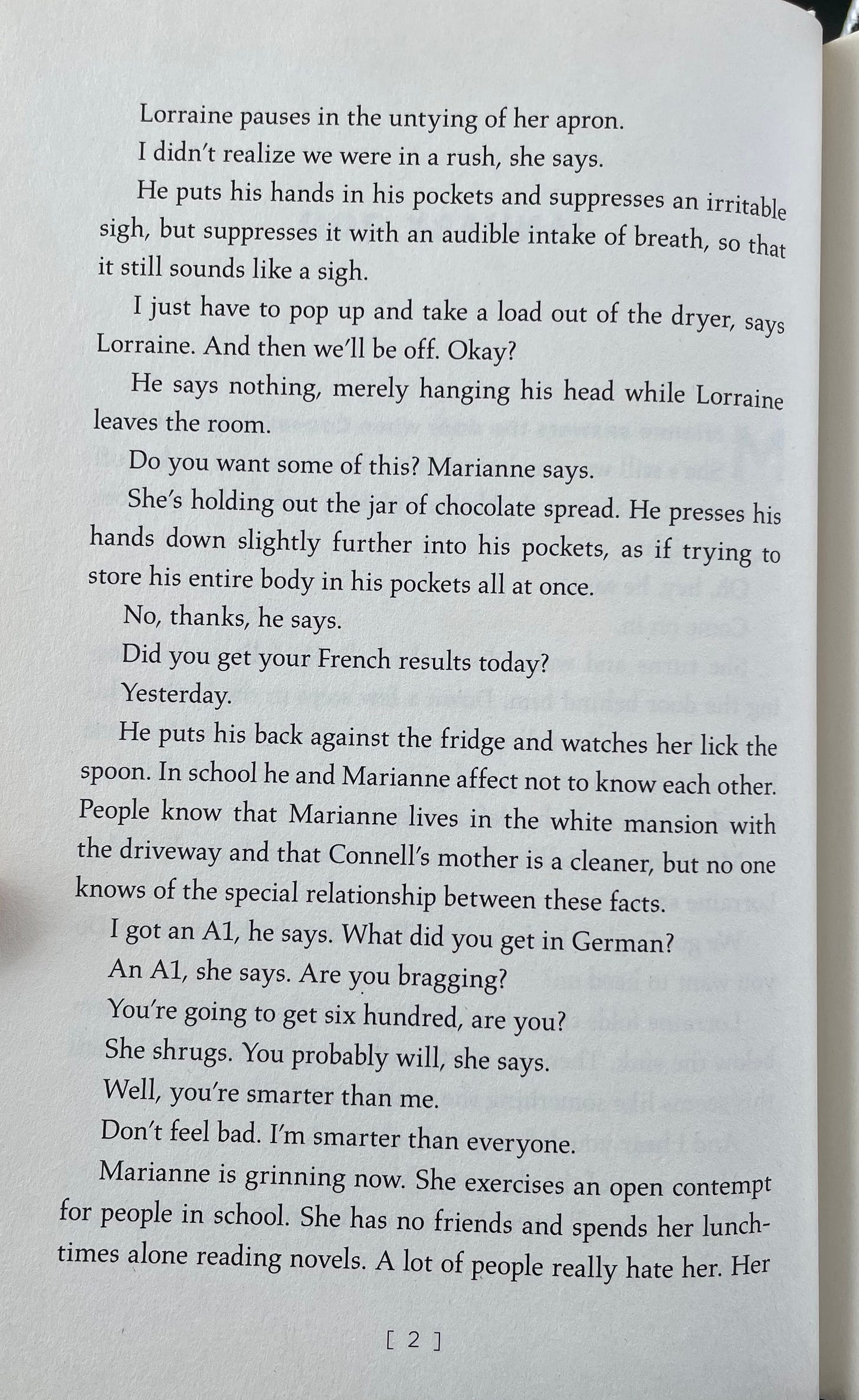

For Rooney, though, it’s about the story. It’s about making your sentences disappear so all there is is story. Here’s page 2 of Normal People.

This page is extremely visual — everything is easy to picture. In contrast, there’s really nothing to picture with the Roth page — it’s all words with no action, movement, or dialogue. That’s why Rooney’s books are also so inhabitable; when you read, you feel like you’re there. I’d love to know what kind of distracting words Roth would’ve used to describe Marianne’s house, as opposed to Rooney’s “white mansion with the driveway,” which is really all you need. Even just “with the driveway” is so good; in addition to being visual, it implies that Connell does not have a driveway, that having a driveway puts you in a certain class.

Anyway, the point is — it’s clean. It’s to the point. And its simplicity belies the work it takes to make it so simple. I think what made Normal People a sensation was partially the confusion it caused in people like me, who when reading were thinking: Is writing like this — allowed? Can we do this?

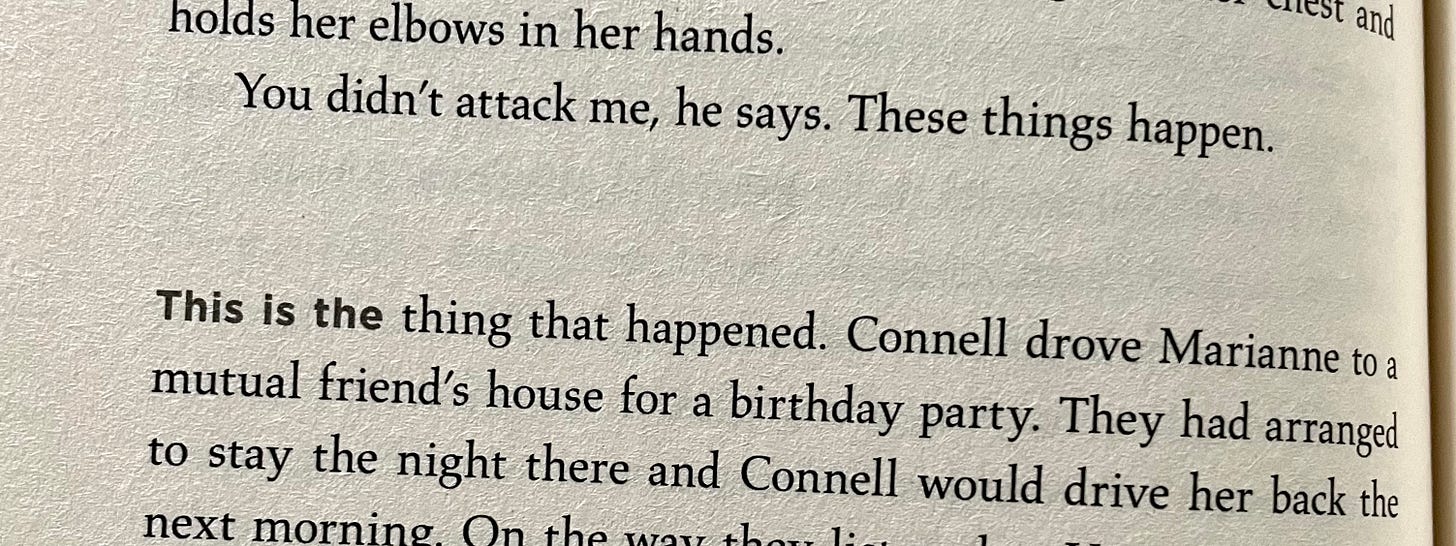

Here’s another example of how Rooney prioritizes story:

“This is the thing that happened.” Yeah! You can write sentences like that! Who the fuck cares? The point is WHAT HAPPENED AT THE BIRTHDAY PARTY. So let’s get there, quick! I guarantee the minute you read “This is the thing that happened,” you forget the sentence ever existed, because all it’s doing is getting you to Point B. Yet if it wasn’t there — if the section began with the following sentence — you might get a little disoriented, like, wait, are we in the past now? Rooney wants you to always be with the story.

Okay, going back to the beginning of the book, I want to talk about the next thing that makes Normal People such a success, which is:

All of the eventual conflict is mentioned or alluded to in the opening chapters.

When people talk about fiction writing, pretty much the number one critique you hear involves the words plot or conflict — i.e., there not being enough of it. I’m going to go ahead and add tension to that, because even though these all mean slightly different things, they’re all part of the singular goal in getting a book to be unputdownable.

Plot is basically just the events of any story. But what makes plot different from just living your everyday life is that plot implies cause and effect, like, a character does one thing which causes something else to happen later on. Conflict is what makes a plot interesting, because it implies that the character has come up against some kind of force or obstacle that is preventing them from getting what they want, or is complicating their life in some way. The way Rooney crafted the conflicts of Normal People is what really sets it apart from other contemporary novels. It’s practically Austen-ian.

When I had just started my third term at Bennington, I had a phone call with my second term teacher to talk about my work the previous term. We then talked a little bit about how my workshop had gone with the new group. “Someone said a weakness in my story was that not enough had changed by the end,” I told her. She got annoyed. “Well, there’s change, and there’s change,” she said.

What she means is, there’s

CHANGE,

and there’s

change.

The same thing applies to conflict. Often, I think we’re pressured to inject “drama” into our writing by throwing in like, death or wives in the attic (especially when we’re told “nothing happens” in our work). But that’s CONFLICT, not conflict. There’s constant conflict in our everyday lives, in all of our relationships, and that’s what Rooney is tapping into.

In the first 10 pages of Normal People, we learn: Marianne’s family is wealthy and Connell’s is not, and more specifically, Connell’s mother Lorraine cleans Marianne’s house; Marianne is unpopular, while Connell is popular; Connell is shy and anxious, while Marianne is bold and contemptuous; Marianne’s family is cruel to her, while Lorraine and Connell are close; and both Connell and Marianne do well in school. All of these simple facts of the book’s universe become causes for later events, over and over again, often manifesting in different ways.

Now that’s all fine, but remember that conflict only works if the characters have something that they want. In Normal People, the overarching, constant-throughout-despite-whatever-else-is-happening-in-that-moment Want that Connell and Marianne both have is to be together. And what’s so great is that desire is pretty much always clear on the page. Their first kiss happens on page 15.

In way less words than what I just did, someone recently explained plot to me as just giving your character what they want and then taking it away, over and over again so that the book becomes a battle for that thing. That is 10000% what Normal People is. Connell and Marianne get together, there’s a rupture that breaks them apart, and this repeats.

Last thing about all this. Notice how the “causes” that I outlined are almost all opposing things? Like, Marianne’s wealth vs Connell’s lack of it. Connell’s abundance of love from his family and friends vs Marianne’s lack of it. This is so ingenious because it puts Connell and Marianne, as people, in opposition to each other — over things that can’t necessarily be fixed or changed by any choice either of them make. It’s just the circumstances of their lives. This is part of what creates tension (thought I forgot about her??).

Tension is an emotion that is symptomatic of conflict. And it’s something that’s talked about less than conflict, although it may even be more useful to think about as a writer, because there can still be tension if there isn’t, at that moment, any real conflict. Take the money thing for example. There are times in Connell’s POV where he’s stressing about money that Marianne doesn’t see, but the reader obviously does. That would be an example of tension, because then you as a reader start wondering if this is going to cause a problem later, and you get kind of stressed out. By the time the actual conflict happens, when Connell loses his job and can’t pay his rent, it doesn’t feel random or thrown in for drama, it feels real. And his decision-making in how to deal with this conflict also feels real and believable, based on what we know about how he feels about money.

Another way to think about tension is something I’m copping from my second term workshop leaders, who explained that “tension happens when two opposing things are both correct.”

So in this example you have Connell, who is sensitive about money and uncomfortable with the idea of being in Marianne’s debt, and then you have Marianne, who has never had to worry about money and is therefore oblivious to Connell’s anxiety. Neither of these things are necessarily wrong, but they can’t coexist — one is going to win out over the other, because eventually (i.e., when Connell loses his job), choices need to be made.

ALL OF THIS makes for an exciting (if emotionally brutal!) read, because the reader is gutted by each conflict and reads on to see how the characters recover.

Ok! So in addition to Normal People being a book that prioritizes story and conflict, it’s also great because:

The story is about something.

By that I mean it’s not just like romance for the sake of romance. There’s a reason why Rooney wants us to pay attention to these particular people. I think about-ness is what makes a book moving and not just good.

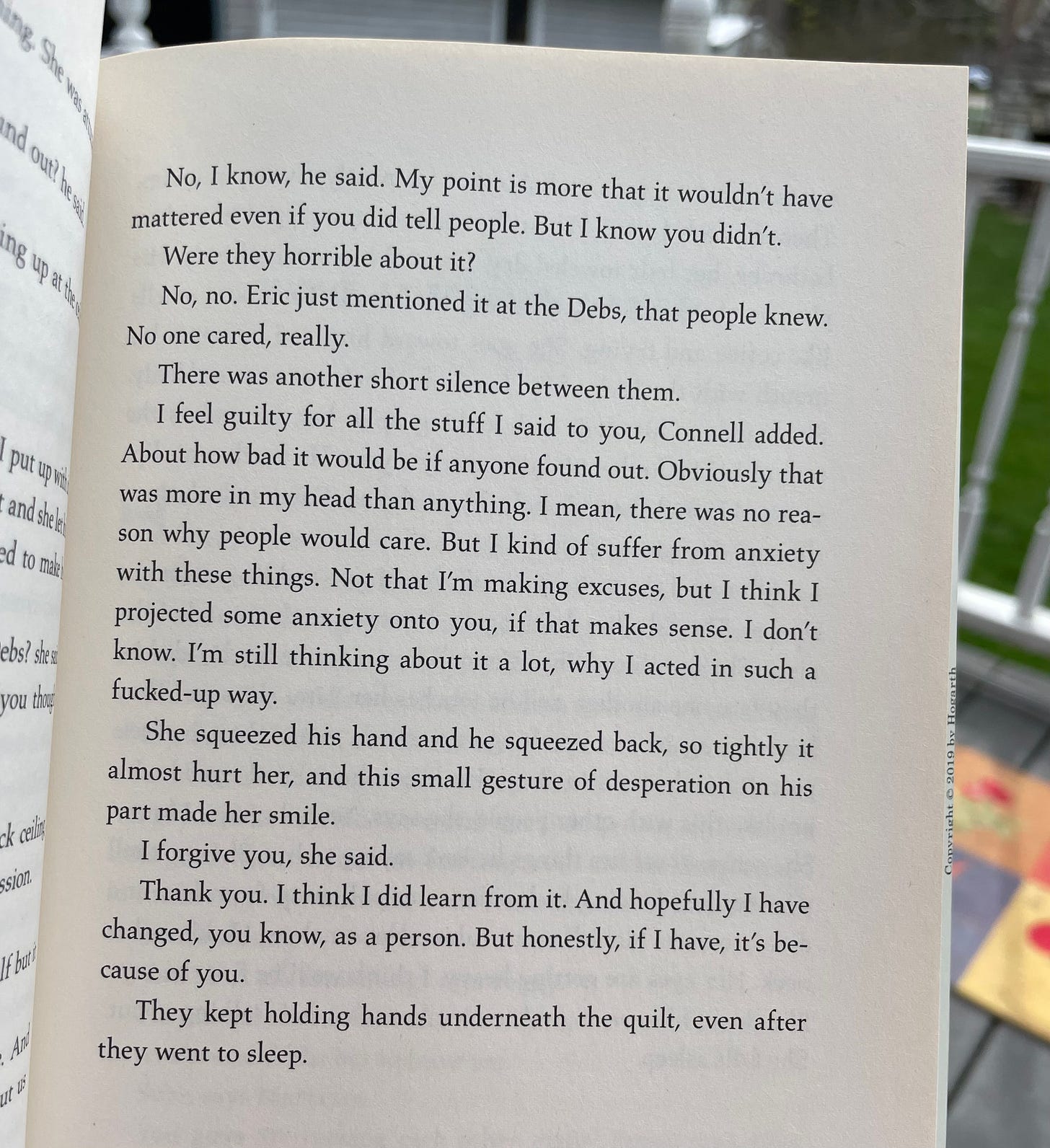

Normal People is about what it means to be made better by your relationship with another person. (Are there any Les Mis fans out here??? ‘To love another person is to see the face of God’???)

Rooney also doesn’t hide this whatsoever or try to make you figure it out on your own. It’s literally the epigraph to the book:

“It is one of the secrets in that change of mental poise which has been fitly named conversion, that to many among us neither heaven nor earth has any revelation till some personality touches theirs with a peculiar influence, subduing them into receptiveness.” — George Eliot, Daniel Deronda

You don’t need to know what that means, going forward, but it’s there, right away, settling into your subconscious. It’s also spelled out here on page 95:

This is basically the point of the book — if I’ve changed, it’s because of you. This is also something that repeats, where Connell and Marianne are conscious of the other’s influence on their life. It’s especially interesting because of how these two differ in terms of how influenced they are by people in general: Connell, for example, cares what everyone thinks of him, while Marianne doesn’t care what anyone thinks of her, yet each has the most powerful influence on the other.

This dynamic is also I think where Rooney gets her title, Normal People. The relationship Connell and Marianne have with each other is the kind of relationship that helps them learn what makes a person good or bad, and what kind of qualities they actually value in those closest to them. Connell and Marianne consistently believe they have things wrong with them, that everyone else is normal and they aren’t — but the trust and love between them is what helps them grow past that insecurity of self, and realize that they have so far just met a lot of not great people.

This clarity of purpose that Rooney has throughout — which is then imbued into the plot — primes the reader for the eventual ending, when it’s spelled out again, hey, remember what this has been about all along? Don’t be mad, because I TOLD you that’s what it was about.

To me, the point of the entire book is who they are after the relationship is over; it’s who they become as a result of each other’s influence. It feels to me like Rooney wants us to picture Connell and Marianne in the future, made different; it’s almost like an origin story for a book we never get to read.

And that’s what makes a book moving, too — when you finish reading and feel that it’s not over, you’ve just left the room. My attachment to these two people leads into the next strength I want to mention:

The characters are lovable.

How many times have you read a Goodreads review that was basically like, “this book is bad because these characters are so unlikable”? Yes, this is annoying. But I also can’t necessarily blame people who have this reasoning.

Again, the goal of a book is to be unputdownable. A book wants to be read! And sometimes we put down a book because we just don’t want to be with this character anymore. We don’t care about what they want, we don’t care about what happens to them, because — we don’t like them. It doesn’t mean the writing is bad. But no one owes it to a writer to stick around purely to enjoy their skill.

Marianne and Connell are great examples of characters who do unlikable things but are still lovable people. And in fact, the unlikable things they do are pretty much direct results of the Established Facts of the Book’s Universe — which means that we want to stick around to see if their characters can grow past these things or not. And because we love them, we’re also double rooting for them to love themselves, which is another central focus of the book, as I’ve mentioned.

Ok now it’s time for:

Small things I want to point out because I’m insane or obsessive or both, whatever.

Their names are symmetrical and pleasing. Marianne Sheridan and Connell Waldron. I love the double Ns in Marianne and Connell, and the N to end their last names. I also love how Marianne and Sheridan both have A and I in them and an “air” vowel sound (Mar/Sher), and how Connell and Waldron both have the O and the L. Yes! I’m insane.

Every chapter starts with a name or pronoun, so we always know whose POV we’re in.

The chapters are dated. They each start with the month+year as well as how many months have passed since the previous section. I’m pointing this out just to say — this is allowed! It is extremely helpful in this kind of narrative (where Rooney is jumping ahead in time, and then going back within the new section to describe events that occurred previously) so that we are situated right away. It also saves Rooney the work of having to use exposition in some other way to explain where we are in time. Just freaking date the chapter and you’re done!

It’s written in present tense, which works quite well with how much she flashes back, because it’s easy to orient yourself in time when you can rely on it being either past or present tense.

By now you’re probably wondering, jeez, is there anything this bitch DOESN’T like about this book? Bestie, of course. But to be honest, the things I don’t like aren’t even things I’d change. Ain’t that life?? To that, I’d also like to share this quote from the foreword to my copy of Joan Didion’s novel Play It As It Lays: “I’m not sure that classics or novels were meant to be flawless. Like golden bowls, sometimes the fascination is in the mysterious crack.”

Ok! Was that a lot?

WELL, THERE’S A LOT MORE, BECAUSE NOW IT’S TIME FOR:

Normal People The Show

I wasn’t born yesterday. I know book-to-film adaptations happen to make money. BUT, I think there’s a bigger more important reason that book-to-film adaptations SHOULD happen — and it’s that writers are great storytellers, and, most of the time, don’t have access to nor the skills required for filmmaking.

The other thing I believe is that actors are able to be great when they have great roles, when they get to play people who are real and lifelike, and, let’s say what I’m really saying, well-written! It’s like how you play a better game of tennis when you’re playing with someone better than you — you can use their strength to make stronger shots yourself. Great actors are great when they can be in great stories.

It’s important to note that Rooney co-wrote the first I think six episodes of the show, so if it succeeds as an adaptation, again, it’s due to her skill.

To write this Substack I watched the show while reading the book, like, I would watch a few episodes and then spend a few days reading to what I had seen and then watch the next few episodes and so on. I wanted to really get an idea of what changed from the book to the show and how.

What I liked about doing this was it became very easy to see what things only literature can accomplish, and what things only film can accomplish.

So I’ll be talking about that — how the story was adapted, and how it was either limited by its medium or advanced by it — as well as admiring the cinematography of the show in general, because let me tell you right now, if you have seen Normal People, there are shots you don’t remember.

So, here is the first and probably biggest way the show adapted the story to fit the screen:

The show corrects Rooney’s narrative style to being linear.

To be honest I quite liked the way Rooney wrote Normal People, and thought it made sense for how she was laying out the story, but, yeah, it doesn’t work in a TV show or movie.

So basically what Rooney did is she would start off a chapter with what’s happening in the current timeline, like, Marianne getting ready to go to Connell’s house one Saturday. Then, as the chapter progresses, it would flash back to what had happened in the previous weeks, like Connell and Marianne sharing a kiss and ignoring each other in school.

The show, however, moves forward in time without going back.

Like — in the show you see (1) Connell asking Rachel to the Debs, then (2) telling Marianne about it, then (3) Marianne dropping out of school, while Rooney writes it as: (1) Connell asks Rachel to the debs, then jump to August when (4) Marianne is sunbathing in her backyard, then flash back to (2) Connell telling Marianne he asked Rachel to the debs, (3) Marianne dropping out of school, etc.

But, that’s just kind of what’s so cool about novel structure, that it doesn’t always need to be linear to make sense, whereas film often has less freedom with that.

In the same vein:

The show spends entire episodes on what are a few lines of exposition in the book.

This is first obvious in how the book and show start. The book starts at Marianne’s house, while the show starts at school, because you lose exposition in sentences like the one in that page 2 excerpt above: “[Marianne] exercises an open contempt for people in school. She has no friends and spends her lunchtimes alone reading novels. A lot of people really hate her.”

While Rooney can just come out and say this at the jump, the show has to spend time showing it visually; we get scenes of Marianne sitting alone reading and spilling yogurt on herself, being bullied by others, and her sassy remarks to teachers. It’s very important that the show spends time doing this, because we need to see who Connell and Marianne are in school before they interact in the scene in Marianne’s kitchen — otherwise we wouldn’t know about the difference in their social status, and there wouldn’t be any tension.

When Connell and Marianne go to Trinity, there are entire episodes that show how each of them spend their time: Connell going home on the weekends, working different jobs, calling Lorraine, studying, getting along with Niall. We see Marianne socializing with friends, speaking up in class, cleaning up her apartment. In the book, all of this is explained in a few lines.

For this same reason, the show also has to create scenes that don’t exist in the book at all; we actually see Marianne break up with Gareth, when the book never mentions it, it just jumps to being three months later and you’re like, ok, guess that didn’t last with Gareth. We also see Marianne call Connell and pointedly say she wants to be friends again, when in the book, it doesn’t need to be so explicitly spelled out.

However, the opposite side of that is:

The show shows you things (in a split second!) that Rooney can only attempt to get you to see.

However good a writer is, literature simply is not visual! And the show totally nails the images and actions that Rooney has on the page. It also capitalizes on feelings Rooney tells us the characters have, showing things in a one-second shot that Rooney has to go to greater lengths to explain with accuracy.

Here are some of my favorites:

There’s always a flip side, though! For all that film can show so quickly, Rooney has the advantage of time; she can draw out moments in a way that film can’t. There is nothing more pleasurable to a reader than to feel that rising action —> climax, and that’s what writing can do really well. A great example of this is when Marianne breaks her nose — in the show, it happens in one moment, but in the book, it’s a long, drawn-out paragraph that tracks the collision of the door and her nose, the noise it makes, the sensation she feels, the movements of Alan, the feeling that her nose is running, the movement of bringing her hand to her face, and finally, at the end, realizing there is blood, and that it must be her own. It’s soooo gratifying to experience the moment this way, as opposed to in the show, where it just happens and then is done.

Still, the show spends time wherever it can, and that leads me to:

It injects emotion into what is bare prose in the book.

I’ve already said this, but I’m saying it again — I love Rooney’s prose in Normal People. The spareness of it actually really lends itself to being read aloud, and in fact the second time I read Normal People, it was out loud to my boyfriend (I’m insane!). But especially with the dialogue sitting on its own the way it does, it almost reads like a script; it’s easy to add inflection and emotion where you see fit. Writers sort of have this eternal struggle between getting a reader to visualize a scene and bogging down the scene with too much information; Normal People is an example of leaning hard to one way, where Rooney is often sacrificing descriptions of facial expression and tone of voice so that the story keeps moving fluidly. However, the fact that she isn’t always ascribing emotions to the characters as they speak means we might read sometimes read their dialogue as cut and dry — and to be honest, I don’t think I fully empathized with Connell’s character in particular until seeing Paul Mescal in the role.

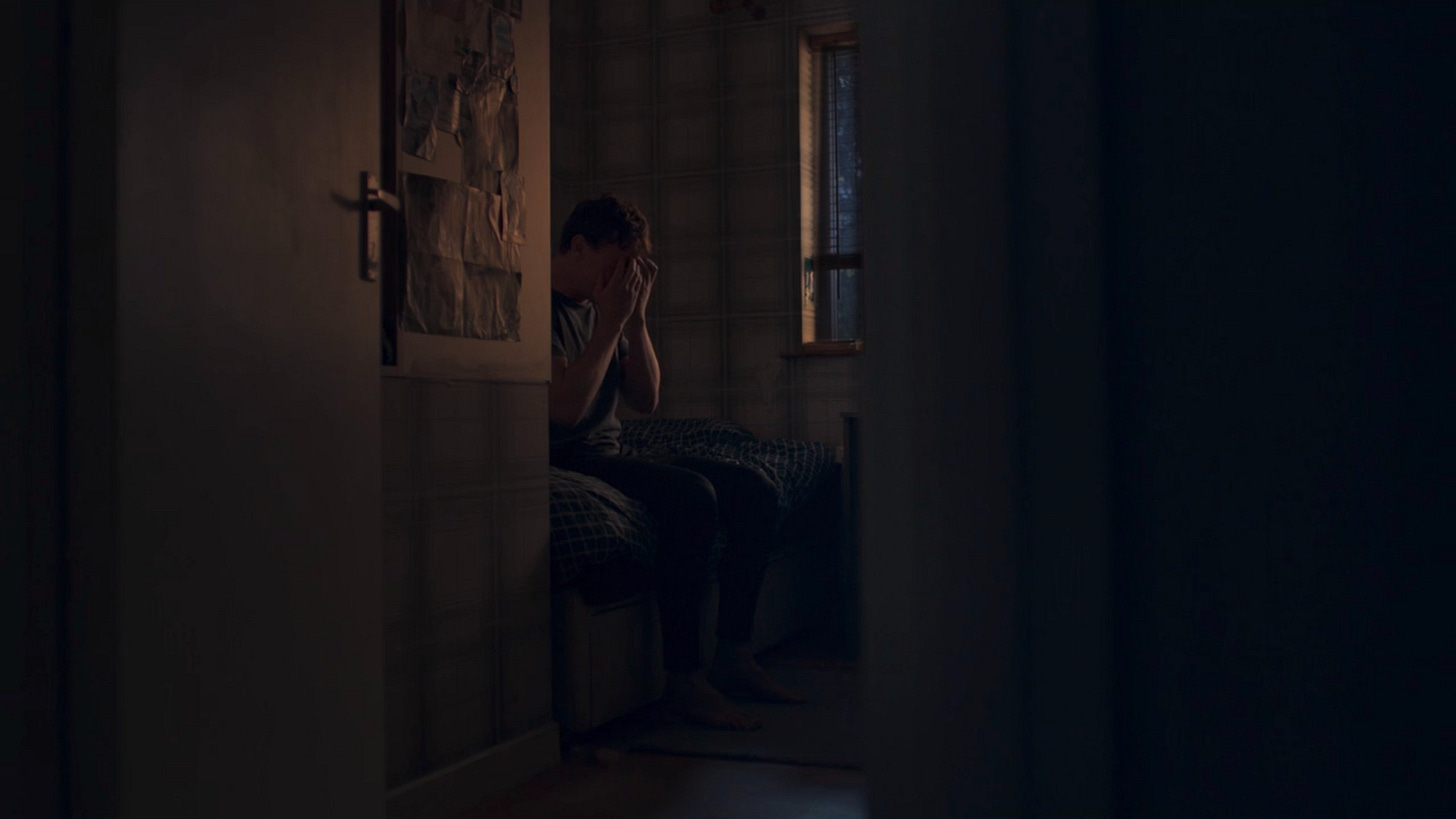

A great example is the scene where Connell’s in therapy. Mescal’s performance is incredible, and the scene is so hard to watch — he’s struggling to get words out through tears, and fully breaks down crying. In the book, though, Connell’s monologue is pretty straightforward, and it’s only until it’s finished and the therapist hands him tissues that there’s any mention he started crying.

Daisy Edgar-Jones of course also brings a fullness to Marianne that isn’t always available to us on the page; her face can run the range of emotions so quickly, like this scene with Connell at a party, where she shifts between cockiness/self assuredness and vulnerability/ insecurity, which is basically the MO of Marianne’s whole character.

The show also doesn’t stick to either Connell or Marianne’s POV.

Rooney’s POV shift every chapter is tidy and helps keep things fresh, but I think if the show did that, it would feel boring and wouldn’t make sense — film already has that inherent objective view from above that a close third person narration doesn’t.

Although the show does at times follow one POV over the other, it still shows the full picture of what’s simultaneously happening in a way that Rooney can’t really do. One example of this is the Italy episode, a chapter that’s in Connell’s POV in the book. Though the show mostly keeps it this way — it follows Connell traveling to Marianne’s, arriving, talking to Helen on the phone, etc — we still get to see things from Marianne’s side that we don’t in the book, like when she goes inside for more wine and Peggy confronts her about the tense conversation outside.

This is a major advantage the show has over the book, because if Rooney wanted us to know what was happening to Marianne, she would have to make Connell go and find out, or else wait until the next chapter when we’re in Marianne’s POV.

This is also really well seen in how the show handles Connell and Marianne’s second breakup. Rooney doesn’t show the breakup in scene, and it takes two chapters to get an explanation of how it happened, because Marianne and Connell both see it differently. In the show, however, we of course see it happen, and it’s clear to us that it’s not what either of them want, because we can see how they both react.

The show also shows the breakup scene more than once, in slightly different ways, to portray the differences in how they each experienced it happening.

Ok, so, that’s my whole bit on why I am a proponent of (thoughtful) book-film adaptations — there’s just so much opportunity to enhance a story. It honestly feels like a win-win situation, because the filmmakers have like, half the work done for them, and the writer gets the satisfaction of having a visual of what was probably always a visual in their own head, but couldn’t always execute through writing.

Now it’s time for the last part of this section, and my favorite, which is:

Cinematography appreciation.

aka special shots I really like.

Who’s still here??? Because it’s time to wrap things up!

I mentioned a very long time ago that I believe we’re all just a little jealous of Sally Rooney, and here’s why.

In Normal People, Sally Rooney leaned in hard to specificity, and she did it with confidence. The writing in Normal People hasn’t a single ounce of uncertainty or insecurity. Yet if any of you writers out there were writing a story that was essentially about, say, a guy not asking a girl to the Debs — would you not feel a little silly admitting it to someone who asked?

And yet there we all were! For a moment there, we were more invested in the Carricklea Debs than in our own lives. There’s actually a meta instance in which Rooney points this out, in Connell’s POV:

“One night the library started closing just as he reached the passage in Emma where it seems like Mr. Knightley is going to marry Harriet, and he had to close the book and walk home in a state of strange emotional agitation. He’s amused at himself, getting wrapped up in the drama of novels like that. It feels intellectually unserious to concern himself with fictional people marrying one another. But there it is: literature moves him. One of his professors calls it “the pleasure of being touched by great art.” In those words it almost sounds sexual. And in a way, the feeling provoked in Connell when Mr. Knightley kisses Emma’s hand is not completely asexual, though its relation to sexuality is indirect. It suggests to Connell that the same imagination he uses as a reader is necessary to understand real people also, and to be intimate with them.”

Um, damn. Reading fiction might be like — empathy training? HM! I mean, it is the specifics of Emma’s life that allow us to relate to her as a person, and therefore to be moved by her story — the same way I’m moved by Normal People.

Maybe we all (read: Me, I) wish we could do that with such ease? Write about the specific, even monotonous, things we experience without needing to be assured that, yes, it is interesting, yes, people will care, yes, it matters, and you should, and actually need to do so?

Well, she’s on to something anyway! Just gonna close now with some of my favorite lines, as the power of literature commands:

There was something so satisfying about the way he studied the table and lined the shots up, and the quiet kiss of the chalk against the smooth surface of the cue ball.

She senses there are things he isn’t saying to her. She can’t tell whether he’s holding back a desire to pull away from her, or a desire to make himself more vulnerable somehow. He kisses her neck. Her eyes are getting heavy. I think we’ll be fine, he says. She doesn’t know or can’t remember what he’s talking about. She falls asleep.

She gives him a look. He feels like the fear has consumed him and turned him into something else now, like he has passed through the fear, and looking at her is like swimming toward her across a strip of water.

Connell looks out the window at the passing landscape: dry yellows and greens, the orange slant of a tiled roof, a window cut flat by the sun and flashing.

Cherries hang on the dark-green trees like earrings.

The sky is a thrilling chlorine-blue, stretched taut and featureless like silk.

Could he really do the gruesome things he does to her and believe at the same time that he’s acting out of love? Is the world such an evil place, that love should be indistinguishable from the basest and most abusive forms of violence? Outside her breath rises in a fine mist and the snow keeps falling, like a ceaseless repetition of the same infinitesimally small mistake.

Connell went home that night and read over some notes he had been making for a new story, and he felt the old beat of pleasure inside his body, like watching a perfect goal, like the rustling movement of light through leaves, a phrase of music from the window of a passing car. Life offers up these moments of joy despite everything.

Did I miss anything? Do you have any book recs that have spare prose and prioritize plot??? Do you think I am predisposed to appreciate Sally Rooney’s writing because I, too, am an air-water cusp? But that’s part of the fun, right? All these weird, specific, mysterious, unknowable reasons why we relate to one another? Why we love something that someone else doesn’t?

This is what happens when I’m away for too long! I digress. This has been—

xxx your twin flame

This is such a good read! I've been fascinated with how accessible Normal People is since I first read it, it's an amazing study at the sentence-level of how to write readable text. And the DFW/Roth dunk is appreciated, it's reassuring to see other people voice these opinions out loud instead of feeling "too dumb" for their work, like I usually do (w.r.t. eyes glazing over reading DFW). I will say Roth's Goodbye Columbus doesn't demonstrate this as much and it makes me curious when he started doing that kind of thing. Like did it just become in-vogue to intentionally complicate prose?

"Roth and DFW, they’re about sentences for the sake of sentences. That’s where all the fun is for them in being a writer. I honestly don’t think they care about their reader at all. Must have something to do with, idk, male ego competitive BS." YES EXACTLY MARRGGGGGGGG